“Everything that happened to me for the last 10 years destroyed my life. I destroyed my life.”

“…I have lived in hell for the past 10 years.”

“I’ll think about this the rest of my life, and beat myself up the rest of my life.”

These dramatic quotes are by Chris Beck, a former Navy SEAL and one-time transgender rights advocate, describing his recent perspectives on his transition and detransition. He is featured prominently throughout a January article in The Atlantic co-authored by trans scholars Daniela Valdes and Kinnon MacKinnon and entitled Take Detransitioners Seriously. The authors use Beck to caution readers about the potential suffering patients may face if they transition and later change their minds and “detransition,” specifically stating that “doctors and clinics need guidelines and services to support people who wish to detransition, but to our knowledge, no formal standards are widely accepted across the gender-care field,” after which they go on to plead for the queer and trans community to support rather than shun detransitioners.

These statements, in and of themselves, are not misplaced. Anyone with a complex gender journey should be supported and have access to all required medical care. However, as the authors themselves state, detransitioning has become a political weapon commonly used to challenge the scientific validity of all gender-affirming care. They even point out that opponents of gender-affirming care “[weaponize] scientific uncertainty.” Dr. MacKinnon himself has written and published several excellent papers on detransitioners, which show a wide diversity of experiences, perspectives on transition, and regret (or lack thereof). Yet, this publication itself risks being used as exactly the sort of weapon it describes because it fails to contextualize its points within prevalent narratives regarding detransition.

Referencing The Atlantic article, journalist Evan Urquhart aptly makes the following analogy:

Why aren’t professional athletes more supportive of athletes whose ACL surgeries fail? Of course, sports media focuses on the careers of athletes who play professional sports, but surely athletes who can no longer play due to an unsuccessful knee surgery are worthy of as much coverage as the athletes who win games? These athletes’ humanity is being neglected! And whether they’re working at a used car dealership, as professional trainers, or high school coaches we, as a society, should pay as much attention to them as we do to athletes whose knee surgeries were a success.

That’s the premise of a recent controversial piece in the Atlantic, with one small change: Replace knee surgery with gender transition, and those sidelined athletes with people who have had disappointing experiences with gender confirmation treatments, and subsequently revert or otherwise shift their gender identification, often known as “detransitioners.””

Anecdotal accounts of detransition shouldn’t influence general access to gender-affirming care for others. When the authors claim, “to many in the trans and nonbinary community, detransition stories—especially those that involve regret—seem to jeopardize half a century of hard-won gains for civil rights and access to health services,” they fail to specify why “many” came to that conclusion. There are well-organized, well-connected communities of radicalized detrans activists that are hell-bent on banning gender-affirming health care for ideological reasons—and, unfortunately, this article outright cites some of their work uncritically, as do many mainstream media platforms. Here, we add the context missing from The Atlantic article and discuss why its omission matters.

Defining Detransition

Detransition is one of those terms with rather fuzzy criteria for “what counts.” A man who transitioned to live as a woman and then undertakes legal, medical, and surgical steps to undo that transition unambiguously counts, but what about someone who re-closets themselves to avoid harassment but still identifies as trans? What about someone who sought medical treatment but stopped upon realizing they’re non-binary rather than a trans man? Is that “detransition?” Does detransition need to be completely voluntary, or does a young adult left with little choice but to detransition because of lost access to insurance or state bans count?

Dr. MacKinnon’s own work broadly defines the word: “when patients stop, or seek to reverse, gender-affirming medical interventions.” He and his coauthors also state that “After medical detransition, individuals may continue identifying as transgender or nonbinary, or they may reidentify with their birth sex (e.g., female or male),” that the outcome is “occasionally temporary,” and that there is wide variability in how detransition is conceptualized by what little research on the topic exists.

This matters because answers to questions like, “How many detransitioners are there?” and “What generalizations can we make about detransitioners?” inherently depend upon to whom the term applies. The far-right defines detransition as a cisgender person thinking they are trans, taking steps to transition, regretting those steps, and reverting to their original (true) cisgender identity. That definition would lead one to assume that detransition is permanent. Yet, the reality is that detransition is often temporary. This is also why some have been using terms like “retransition” instead; the term implies other options beyond a one-or-the-other dichotomy and outside the binary.

To contextualize The Atlantic article, we talked to detransitioners and retransitioners who would count under just about any definition: Ky Schevers and Lee Leveille, the duo behind Health Liberation Now!, who advocate for equitable access to health care and expose the weaponization of detransition narratives. Both had been significant players in detrans (a popular abbreviation for “detransition/detransitioned/detransitioner”) communities. Ky and Lee both have first-hand experience with the context ignored in this piece.

Ky, who identifies as a transmasculine butch-a term which, in lesbian culture, denotes someone whose gender expression and traits are viewed as ‘typically masculine’- and uses she/her pronouns, started transitioning to male in college. Her detransition included participating in what she describes as a transphobic detrans subculture. Under the name CrashChaosCats, Ky engaged in anti-trans activism as a detransitioned radical feminist from 2013 to late 2019. Ky used to work hard to get into the media to shift the public conversation about transition and detransition. As someone who was harmed by such groups and caused harm while she was part of them, Ky knows the damage detrans groups and activism cause. She deeply regrets how she manipulated the media to spread anti-trans propaganda and promote conversion practices. She agrees with trans people who criticized the articles she appeared in, particularly Katie Herzog’s infamous 2017 article, The Detransitioners, which is still cited widely by anti-trans activists and used as propaganda.

Lee, who uses she/her and he/him pronouns, was the founding Vice President of the Gender Care Consumer Advocacy Network (GCCAN), a self-proclaimed “non-partisan, non-ideological collaboration between trans and detransitioned people to advocate for better health care.” However, he resigned in protest after seeing the impact his and similar groups have on trans health narratives.

Contextualizing Detransition in the Media

“Detransition” stories started emerging alongside an increase in the visibility of trans people in the last decade and with a shift from gatekeeping trans health care to gender-affirming, informed consent-based health care. The rise of YouTube and Tumblr in the 2010s created new spaces and communities for trans people. In June 2014, Time Magazine’s cover featured Black trans actress Laverne Cox with the declaration that the U.S. has reached the “transgender tipping point.” Cox was also one of the first visible trans people to push back on the invasive questions about genitalia and surgeries trans people often publicly endure. That same year, President Obama’s Affordable Care Act barred insurance companies from excluding those with preexisting conditions—and his administration’s ruling on Section 1557 of that same law explicitly barred blanket exclusions on trans-related health care as a form of discrimination. For the first time, thousands of trans people could finally afford health insurance and gender-affirming hormones and surgery. LGBTQ people have finally seen themselves on TV screens, with representation increasing year to year.

In 2015, after losing the fight over gay marriage, the American religious right shifted its attention to religious exemptions and trans people. Spurred by groups like Family Research Council and Focus on the Family, massive numbers of bills began targeting transgender bathroom rights and coverage of transition-related care. These bills were, even then, explicitly testing the waters as part of a broader movement opposed to the very concept of transgender people, and aimed, in some form, to mandate that sex is determined at birth and immutable, with the goal being the eradication of transgender identity. The Trump campaign (and later the Trump administration) aided and abetted these goals from the beginning.

“Trans and gender identity are a tough sell, so focus on gender identity to divide and conquer,” said Meg Kilgannon at the 2017 Values Voter Summit, the annual conference presented by Family Research Council. “For all of its recent success, the LGBT alliance is actually fragile, and the trans activists need the gay rights movement to help legitimize them. Gender identity on its own is just a bridge too far. If you separate the T from the alphabet soup, we’ll have more success.”

To this end, the Christian Right started engaging anti-trans feminists as an alliance of convenience around 2017. The bathroom myth-a moral panic claiming non-discrimination laws will lead to male predators in women’s restrooms-was entirely concocted by the Right “as a way to avoid an uncomfortable battle over LGBT ideology, and still fire up people’s emotions,” and, indeed, there is no evidence to support the myth outside of manufactured hoaxes. The radical feminist organization Women’s Liberation Front (WoLF) received a $15,000 donation from the Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF) to support a legal suit challenging U.S. school policy allowing trans students to use the bathroom aligned with their gender. By the end of Trump’s presidency, trans people were banned from serving in the military; homeless shelters, other federally-funded housing services, and the DHHS rolled back non-discrimination policies that protected trans people. President Trump—with the support of the American College of Pediatricians, cosigned by Susan Bradley, and the then-nascent Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine—went so far as to rule in favor of excluding trans people from Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act, undermining Obama’s final rule—by erasing the concept of transgender people from definitions of sex and gender, thereby allowing insurers to deny care again. Had Trump won a second term, this policy would have persisted.

Along with manufactured myths came new, evocative terminology. Around 2016, the term “gender ideology,” historically used by the Catholics, started to be used by anti-trans websites such as 4thWaveNow and was increasingly circulated in GC (gender critical) spaces. In 2018, Littman coined the pernicious (and thoroughly discredited) phrase rapid-onset gender dysphoria, or ROGD, to describe the idea that transness in American adolescents can be caused by social contagion. In addition to creating panic around youth catching transness, Littman has studied detransition, drawing data from ideologically biased databases to conclude that “detransitioners have complex problems not solved by transition.”

Detransition is far from a taboo subject in the mainstream, where it is commonly invoked to discredit gender-affirming care. Shortly after Caitlyn Jenner’s July 2015 Vanity Fair cover, a wave of thought pieces speculated that she might detransition due to “sex-change regret.” For her dissertation research, Ph.D. student Vanessa Slothouber collected 50+ mainstream media articles published between 2015 to 2018 and speculating on Jenner’s detransition, most centered around ‘regret,’ limiting access to gender-affirming care, and conspiracy theory-like claims that detransitioners and their allies are being silenced.

To be clear, the act of detransitioning is not in itself transphobic or anti-trans, but mainstream coverage of the phenomenon is. Stories about people having a bad experience with transition are more relatable in the mainstream and appeal to a large audience of people who want to believe that gender affirmation does not work. The specific type of detrans narrative popular in news media argues that trans people can become cis if they just try hard enough, because these narratives treat being trans as a “treatable” mental disorder, best approached by forms of conversion therapy. Reports about the supposed harm that puberty blockers do, which do not consider the irreversible damage of incongruent puberty we regularly force trans youth to undergo by restricting access to gender-affirming health care, are grounded in such perspectives.

Chris Beck

The article’s use of Beck, his experiences, and his words surprised Beck himself, who strongly objected to being featured, without his knowledge or consent, in an article he could not even read due to a paywall. The article also introduces Beck using his former name rather than his currently preferred one.

Valdes and MacKinnon criticize centrist, liberal, and leftist press outlets for not covering Beck’s detransition while themselves failing to note that the “latest chapter” in his life follows on the heels of his radicalization by far-right Christianity, alongside vitriolic opposition to critical race theory and vaccines. The many outlets on the political right that have covered his detransition also omit these details. Further, Valdes and MacKinnon claim that Beck “is not against trans people or gender-related medical care” while linking Beck’s interview with anti-trans pundit Robby Starbuck. A quick search of Beck’s Twitter reveals this claim to be demonstrably untrue. Beck is plainly opposed to gender-affirming care and believes the modern trans rights movement is a scam. He routinely spreads misinformation about trans health care while adopting the language of the far right. Claiming to not be against trans people or gender-affirming care is the standard plausible deniability line that anti-trans activists use to get their perspective in the media, in much the same way anti-vaxxers like Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. like to claim that they are not just “not antivaccine” but “fiercely pro-vaccine.” There is heavy overlap between anti-trans and anti-vaxx circles, particularly among parent activists, some of whom goes as far as to say they are not anti-trans; they’re pro-detransition.

Anyone can claim they’re not transphobic, not homophobic, not racist, or not antivaccine. The measure of whether someone is anti-trans is what they do, not what they say—and what Beck does is clearly anti-trans. Covering Beck while glossing over that is fundamentally misleading.

Impact

Our Duty, a group of anti-trans parents who want “100% desistance” for trans youth and to eliminate medical transition, quote Valdes and MacKinnon’s writing in The Atlantic article in a pamphlet on transition regret. Hands Across the Aisle Coalition, an organization that connects anti-trans radical feminists with the Christian Right, counts infamous transphobe Kellie-Jay Keen-Minshull, AKA Posie Parker as a member, and supports anti-LGBTQ groups in legal actions against trans rights, has shared The Atlantic article on Facebook, with the single comment: “Progress.” Parker’s latest rally in Australia attracted a crowd of straight-up neo-Nazis, whom Parker welcomed with open arms, following a pattern by which Parker solicits alliances with far-right militants. The Christian Post has used the article to argue against all gender-affirming care.

MacKinnon, an assistant professor of social work at York University who has coauthored research about detransitioners, cannot plead ignorance to the harm this article is doing. One of the participants in his study discusses how transphobic media coverage of detransition negatively impacted them. Yet here, there is no mention in The Atlantic of the damage anti-trans media portrayals of detransition do. Legislators and attorneys frequently use media pieces to argue for or attempt to protect bans on gender-affirming care. Anti-trans amicus briefs and expert reports regularly reference articles from The Atlantic and other media outlets, such as the New York Times and Newsweek. Daniela Valdes, a doctoral candidate in history at Rutgers University, has, to our knowledge, done no prior work on detransitioning; why is it that none of MacKinnon’s colleagues who have done research in the field are involved in this current media stint? Why is this article so diametrically opposed in tone to MacKinnon’s other publications? The abstract of his 2021 paper, Preventing transition “regret”: An institutional ethnography of gender-affirming medical care assessment practices in Canada, advises:

When a person openly “regrets” their gender transition or “detransitions” it bolsters within the medical community an impression that transgender and non-binary (trans) people require scrutiny when seeking hormonal and surgical interventions. Despite the low prevalence of “regretful” patient experiences and scant empirical research on “detransition”, these rare transition outcomes profoundly organize the gender-affirming medical care enterprise…We conclude that regret and detransitioning are unpredictable and unavoidable clinical phenomena, rarely appearing in “life-ending” forms. Critical research into the experiences of people who detransition is necessary to bolster comprehensive gender-affirming care that recognizes dynamic transition trajectories, and which can address clinicians’ fears of legal action—cisgender anxieties projected onto trans patients who are seeking medical care.

There is no evidence of an epidemic of mass detransition unless Republican lawmakers get their way and forcibly detransition both trans kids and trans adults. Missouri has set the precedent, and Florida just passed SB254, which bans care for minors and allows the state to take custody of youth being “subjected” to gender-affirming care. Research is overwhelmingly focused on rare cases of regret when it should focus on building supports for trans and detrans people alike.

The “Rising Detrans Numbers” Trope

The number of detransitioners continues to increase, mainstream media outlets, including The Atlantic, warn. However, those numbers are entirely dependent on how detransition is defined. Valdes and MacKinnon characterize detransitioners as “people who reverse a previous transition,” though not all detransitioners “reverse;” some course correct. Detransitioners may still assert an identity different from the one they were assigned at birth. Detransition-and MacKinnon’s own research supports this- frequently does not mean going from trans to cis. And yet again, detransition is not necessarily a permanent or desired outcome. Every transgender minor will be forcibly subjected to medical detransition in no less than sixteen states at the time of writing.

The Atlantic warns:

Although many detransitioners do appreciate the opportunity for self-discovery that their transition provided, others would not take the same steps if they could go back in time.

This is stated without citation; the burden of proof here is on the authors—who also don’t point out that many detransitioners later transition again. Thus, this warning paints an incomplete picture of the possibilities. Before this, MacKinnon had not framed his research results as challenging concerns about transition regret. In a 2022 study with Drs. Hannah Kia and Travis Salway, he concluded:

…clinicians should investigate patients’ feelings and care needs without assuming people experience their initial transition as a “mistake.”

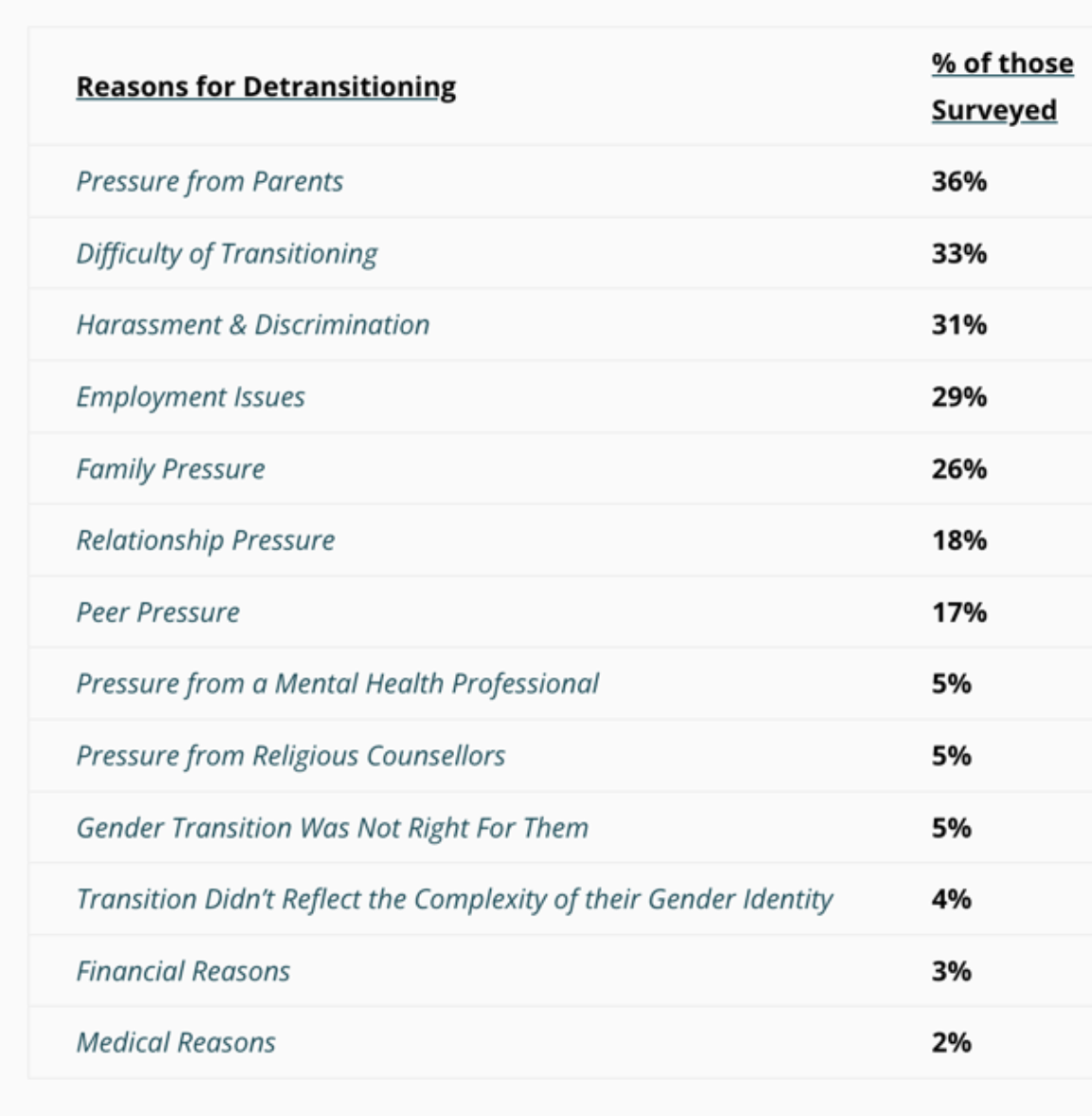

Detransitioner statistics are often falsely inflated by counting people who temporarily stopped gender-affirming hormones, those who always planned to stop once they felt affirmed, and patients lost to clinic follow-up. For example, it is common for people to take testosterone long enough to get permanent changes, such as voice drop and bottom growth, and stop. Ky reports that this is what she did; most people who do so still identify as trans or nonbinary and are happy with the results of taking testosterone temporarily. We should not assume that people who stop gender-affirming hormones are detransitioning, stop identifying as trans, and/or are unhappy with their experience of taking hormones. Their plan from the beginning may have been to stop at some point. There are many additional reasons for detransitioning, as noted below in a table derived from the 2015 United States Transgender Survey (USTS) from the National Center for Transgender Equality, comprising 27,715 participants:

For post-surgical regret, frequently conflated with detransition in the mainstream media, rates are around 1% or less (0.3 to 0.6% in a retrospective review of 6,793 people who received care at one gender clinic between 1972 and 2015; 0.3% in a 2023 review of 1989 people who underwent 2,863 gender-affirming surgery procedures between 2016 and 2021.) The Atlantic article itself links Tang et al. 2022, who report a rate of post-operative regret over 7 years (2013-2020) of 0.95% (2 patients), with neither regretful patient undergoing reversal surgery. By contrast, a 2018 systematic review found a regret rate of up to 20% for total knee replacement surgery. Another study on surgical regret notes that self-reported patient regret was “relatively uncommon” at around 14.4%. Suppose gender-affirming surgical regret rates were 14.4%: with the amount of handwringing around gender-affirming care, would that rate of regret still be characterized as “relatively uncommon”? Transition regret attributed to doubt about gender identity is expressed by 0.09% of people in one study, 0.3% in another, a rate of less than 1% in a third, and 2.4% in a fourth.

Still, The Atlantic warns:

…older studies may not adequately predict outcomes for today’s far larger, more diverse trans and gender-questioning population.

A larger pool with more diversity is not directly correlated with detransition, a truth that does not fit into the authors’ narrative, never mind that high detrans numbers have, at least in one instance, been fabricated. For all we know, the detrans rate might be lower for today’s more modern population. That one instance, of course, spread the rumor of the existence of “100s of detransitioners” like wildfire. Valdes and MacKinnon link Roberts et al. 2022 to assert that “Another U.S. study published last year found that, for reasons that remain unknown, 30 percent of patients who begin gender-related hormone treatment discontinue it within four years.” However, this study’s statistics are misleading as it only looked at patients receiving gender-affirming hormones through one insurance plan. Anyone under a different plan or without insurance was counted as having discontinued treatment, which more than likely inflated numbers. In a statement that refutes the premise that this “newer” cohort of trans patients doesn’t know what it’s doing, the study also reveals:

Patients who were younger than 18 years of age when starting hormones were less likely to discontinue use than patients who were 18 years of age and older.

Roberts et al. continue, under Discussion (emphasis ours):

We noted a higher hormone continuation rate among TGD individuals younger than 18 years old at the time of first use of gender-affirming hormones compared with those aged 18 years and older when starting hormones. This has not been documented in previous studies… Regardless of the reason for the higher hormone continuation rate among TGD youth, this finding provides support for the idea that TGD individuals below the age of legal majority, with the assistance of their parents or legal guardians and health care providers, can provide meaningful, informed assent for gender-affirming hormones and do not appear to be at a higher risk of future discontinuation of gender-affirming hormones because of their young age alone.

Valdes and MacKinnon continue to caution,

The need to know more about detransition is all the more urgent amid a surge of new patients lining up at gender clinics.

Fearmongering about “surges” is tired and implies that detransition is a bad outcome to be avoided. The reality is more complicated; transitioning and detransitioning can be a positive or neutral experience overall. Detransition does not equal suffering, a bad choice, or regret, nor does it imply that being transgender is a phase. Even when it does equal regret, that feeling might be temporary: a person’s interpretation of their experience can change over time, especially if it is connected to external factors like conversion therapy or ideological detransition. As noted by Turban et al. 2021, a study cited in The Atlantic article,

Qualitative responses revealed that the term “detransition” holds a broad array of possible meanings for TGD people, including temporarily returning to a prior gender expression when visiting relatives, discontinuing gender-affirming hormones, or having a new stable gender identity. Participants’ responses also highlight that detransition is not synonymous with regret or adverse outcomes, despite the media often conflating detransition with regret.

The Atlantic article reasons that the surge is caused by a move to gender-affirming care practices, “greater social acceptance of gender-nonconforming people, and an accompanying expansion of the pool of potential patients for gender care.” Yes, yes, and no. There is no “accompanying expansion of the pool” to include gender nonconforming people. Gender nonconformity can be a facet of gender identity, but many gender nonconforming people are cisgender. It is a glaring omission for trans historians not to mention Kenneth Zucker and his desistance research of gender nonconforming cis gay kids who grew up to be-surprise!- cis and gay and not trans-more on that later. We’ve taken gender nonconformity out of the pool. The authors may really mean people who identify outside of the binary, but why not say it that way? They have the language and capacity to know the difference between gender nonconforming and gender diverse (nonbinary, genderfluid, and other identities that fall under the trans umbrella) people, as evidenced in the article. The use of the gender nonconforming terminology here, instead of gender diverse, indicates either an editorial change or the authors’ dated position.

Cohen et al. 2022, a study of 68 U.S. trans youth accessing gender-affirming care, notes,

…only one individual reported regret for having undergone treatment, consistent with previous reports that regret is a relatively rare outcome.

The authors mention this study for its finding that 29% of the youth shifted treatment requests concerning hormones, surgeries, or both. Many people shift their treatment requests in different aspects of health care. This is not unique to gender-affirming care, and attempting to argue otherwise is a gross injustice to psychiatric survivors and chronically ill and/or disabled people. Additionally, 45% of that 29% reasserted their treatment request, and only 3 youth shifted treatment requests after starting gender-affirming hormones. As the authors write:

Notably, the most common shift profile in our cohort was shift profile 2, where the request was re-established (9 of our 20 youth). In fact, many youth who shift away from a request may do so temporarily, and later come back to the request.

Valdes and MacKinnon admit that detransitioners have varied experiences. So why do numbers matter? Suppose we’re not discussing limiting care, a purpose for which anti-trans detrans narratives are routinely employed. Why do we need to specifically consider detrans people instead of doing what gender-affirming care providers already do: gender-affirming care without an endpoint in mind? Why is an emphasis on an influx of patients who may or may not even be that different in the first place?

Intentionally or not, the article suggests that with more trans people accessing treatment, there will be a higher regret rate. Dhejne et al. 2014, linked in The Atlantic article, show the opposite is true. This study analyzed all applications for gender-affirming surgery in Sweden between 1960 and 2010 and found that 2% applied to return to their sex assigned at birth. The regret rate, which was measured as “people who received a new legal gender and then applied for a reversal to the original sex,” decreased significantly over the period of the study:

The risk of regretting the procedure was higher if one had been granted a new legal gender before 1990. For the two last decades, the regret rate was 2.4 % (1991–2000) and 0.3 % (2001–2010), respectively. The decline in the regret rate for the whole period 1960–2010 was significant.

It is essential to stress that the numbers shouldn’t matter. What should matter is ensuring everyone has access to the care they need, both before, during, and after transition (or detransition, or during retransition, etc.) It is impossible to predict who will detransition. Further, it’s also impossible to predict which detransitioners will transition again later in life. There does not appear to be any consistent pattern, despite what anti-trans activists claim. Everyone is better served by creating more comprehensive support networks across a person’s pathway.

Mainstream media portrayals of detransition do not work towards these goals. Instead, they rely on antiquated tropes that harm detransitioners and happily transitioned trans people.

The “Not Trans, Just Gay” Trope

According to The Atlantic,

But some detransitioners realize, after years of living as a trans person, that they are instead lesbian, gay, or bisexual.

The statement ignores the fact that most trans people are queer-that is, their sexual orientation is something other than straight, or heterosexual. “Queer” and “trans” are not mutually exclusive, and no one operating in good faith would imply otherwise. Sexual orientation is different from gender identity. Valdes and MacKinnon’s supporting evidence comes from someone known to operate in bad faith: Lisa Littman. They cite Littman’s 2021 study of 101 self-identified detransitioners, which skewed its results much in the same way her much-maligned 2018 ROGD study did. Like she did when developing the concept of ROGD, which recruited from blogs known to be hostile to transgender youth care, Littman’s detransition study relied upon radical feminist sites hostile to transition being snowballed into the recruitment pool. Interestingly, internalized homophobia was not on the list of things Littman initially surveyed for. Ky notes that Littman’s recruitment pool had to add it because several participants were forming that opinion, likely due to their new radical feminist politics.

Ky was one of the participants represented in this dataset. As a participant, she felt that Littman was fishing for evidence for her ROGD theory and exploiting the detrans community to prove it. Many of the questions Littman asked were difficult to answer in a way that accurately reflected Ky’s experiences of dysphoria, medical transition, and detransition. To Ky, the questions were written by someone without understanding or knowledge of gender dysphoria, transition, detransition, or what it’s like to live as a trans person. In her own words:

The detrans radfem community didn’t believe in ROGD. We saw it as something anti-trans parents like 4thWaveNow made up, and we had a very rocky relationship with parents like 4thWave. We often got into conflict with her and other “ROGD” parents. We emphasized how our gender dysphoria was the same as other trans people’s. Ex-gay people don’t act like their queerness is different from other gay people, so why would ex-trans radfems act their gender dysphoria was different from other trans people’s? The point in both cases is to “prove” that all gay or trans people can become ex-gay or ex-trans people, respectively. So Littman asked a bunch of detrans radfems questions to find evidence of something even we didn’t believe in.

We all did believe that gender dysphoria could be caused by internalized misogyny and homophobia. The detrans radfem stance on dysphoria was that it was caused by internalized misogyny, homophobia, and/or trauma. A majority of detrans radfems identify as lesbian or bisexual. I’m sure that when I took that study, I said something about how my dysphoria was rooted in how I couldn’t accept myself as a lesbian. So it’s no surprise that she found many people saying that their dysphoria was caused by internalized homophobia.

The “not trans but gay” trope is inextricably linked to Dr. Richard Green, a founding committee member and one-time president of HBIGDA (now known as WPATH), who created the blueprint for Gender Identity Disorder of Childhood (GIDC). In 1987, Green wrote The “Sissy Boy Syndrome”: The Development of Homosexuality based on a 15-year study of 66 gender nonconforming boys he treated as a Psychiatrist at UCLA’s Gender Identity Research Clinic who stated that they wished to be girls. 75% of them grew up to be gay men. The UCLA clinic’s goal was to perfect conversion therapy; kids were only allowed to transition if all coercive conversion attempts failed, which they regularly did. One of Green’s former patients, Dr. Karl Bryant, grew up to be gay and not trans and considers himself a survivor of Green’s conversion therapy treatment:

Bryant grew up to be a happy, successful gay man, and he refuses to speculate how, or whether, things would have been different if his parents had allowed him to follow his fervent childhood wish to be a girl. But his “happy outcome,” he says, is despite, not because of, Green’s interventions. The study, he says, gave him the lasting impression that “the people closest to me, and that I trusted the most, disapproved of me in some profound way.” He says it’s hard to overstate the harm that such knowledge can inflict: “The study and the therapy that I received made me feel that I was wrong, that something about me at my core was bad, and instilled in me a sense of shame that stayed with me for a long time afterward.

Bryant has written about GIDC and the goal of treatment, which was to eradicate or reduce boys’ femininity and promote forms of masculinity. Bryant endorses his support for the gender-affirmative models of care:

Alternative approaches (e.g., Menvielle & Tuerk, 2002; Children’s National Medical Center, 2003) that do not define the gender-variant child as the problem have begun to appear and are beginning to infiltrate terrain that was once held solely by GIDC researchers and clinicians. Their reorientation to gender-variant children has, for example, redefined the problem not in terms of the gender variance itself but instead in terms of the stigma to which gender variant children are subjected. As such, the goal of mental health service provision becomes helping children and their families cope with stigma instead of trying to change gender-variant behavior itself (e.g., Menvielle & Tuerk). It is these kinds of programs that hold out the greatest promise for a future where mental health professions play a key role in providing meaningful support to gender-variant children.

Valdes and MacKinnon state the need for guidelines and clarity without acknowledging that the guidelines we followed for decades– conversion therapy efforts that were intensely damaging even when they allegedly “worked” –failed to keep up with best practices and science and have been discredited. Medicine has moved towards a model of care that actually works and supports patients: gender affirmation. Despite this, conversion therapy continues to be heavily practiced and promoted, wrapped up and presented shiny and new every few years, most recently as gender-exploratory therapy.

The “It’s Mental Illness, You’re Not Trans” Trope

According to The Atlantic,

Other detransitioners come to discover that what they thought was only gender dysphoria may have reflected a more complex picture—perhaps including a neurodivergence, the aftermath of a past trauma, or some other mental-health challenge.

Vandenbussche’s 2021 detransition study is cited to support the claim that dysphoria may instead be an overlooked mental illness and to support the idea that detransitioners face social rejection. Vandenbussche tapped some of the same communities as Lisa Littman’s detransition “research” and other trans antagonistic spaces (Post Trans, r/detrans, and “private Facebook groups”). Vandenbussche’s survey drew from biased sampling pools, with many respondents endorsing radical feminist or gender-critical views, a salient point that goes unmentioned in the study’s Discussion section. This skews the study data and does not make for a representative sample. It would be like a study on vaccines drawing solely from anti-vax websites to ask about a link between vaccines and autism; one would expect the results to be skewed to the demographic surveyed and not representative of general experiences and sentiment. Vandenbussche, one half of Post Trans, has presented for trans eliminationist organization Women’s Declaration International, and both she and Littman are heavily quoted in anti-trans testimony.

If gender dysphoria is “just” an undiagnosed mental health issue, it follows that we should shift the focus to psychotherapy and oppose gender affirmation. This is the explicit position of organizations like Genspect and the Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine, who work to advance this consensus. However, even Vandenbussche’s study doesn’t support this conclusion; she found the most common reason for detransitioning- endorsed by 70% of study participants- was “my gender dysphoria was related to other issues.” As noted by Martin 2022, Vandenbussche does not specify what those “other issues” were;

Moreover, it does not deny the persistence of dysphoria, it only states that medical transition was not a panacea (something we have already discussed). Only in the 14% “mixed bag” is it mentioned that the reason was that gender dysphoria had disappeared.

Despite the dearth of evidence that mental concerns lead to identifying as trans, this is a common argument perpetuated by those who oppose gender-affirming care. Research finds that as many as 41.5% of trans people have a mental health diagnosis or substance use disorder, but this is widely accepted to be a consequence of minority stress, the chronic stress from societal stigma and discrimination experienced by trans people due to their identity and expression.

Lee used to be in one of the private Facebook groups Vandebussche recruited in, a political space connected to Ky’s prior hangouts, which was exclusively AFAB-allowing entry only to those assigned female at birth- and geared toward radical feminists. According to Ky, the “private Facebook groups” were run by detrans radfems and TERFs (trans-exclusionary radical feminists).

In those communities, the general belief is that gender dysphoria, in AFAB people at least, is a kind of dissociative coping mechanism rooted in past trauma and internalized sexism. There’s no way you could survey those communities and not get many people saying they transitioned due to trauma. Often people join those groups because they’ve come to believe this and are often trauma survivors hoping that if they adopt radical feminism and detransition, they’ll be able to heal. The thing about neurodivergence ties into beliefs about AFAB people transitioning as a form of internalized sexism. It was common among detrans radfems I knew to believe that it was socially more acceptable to pass as an autistic or otherwise neurodiverse man than to live as a neurodiverse GNC woman.

The ”Rushed into Transition” Trope

Valdes and MacKinnon report that Beck has “urged trans youth to slow down in order to avoid his fate.” This statement implies that people detransition because of rushing into transition, ignoring the notoriously slow process of getting into a clinic and the many barriers that come with attempting to access gender-affirming health care. Curiously, the concept of detransitioning is linked to gender-affirming, informed consent practices when those practices were largely unavailable as an option at the time many detransitioners first embarked on their gender transitions. Conversion therapy and barriers to care were the norms for decades, which means many detransitioners initially transitioned at a time when there was more gatekeeping. Even Keira Bell, a detransitioner known for suing the UK’s Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) at the Tavistock and Portman clinic in London, had to undergo psychological assessments before accessing puberty blockers at 16 years old. Her lawsuit, with a legal team helmed by Paul Conrathe, who had previously represented anti-abortion cases in which he challenged Gillick competency, and whose expert witnesses included Paul Hruz, has had devastating effects on gender-affirming care access for trans youth and launched Dr. Hilary Cass’ NICE reviews, which have had further scathing effects on trans health care.

And though the research concludes low regret rates, specific study authors maintain the need for a gatekeeping approach. Butler et al. 2022, a British study of 1,089 young people referred to gender clinics between 2008 and 2021, notes a very low rate of detransition, yet calls for more assessment. Van der Loos et al. 2022 found that only about 2% of young trans people discontinued gender-affirming hormones. The Atlantic article authors note that the patients in the study had “mental-health support and diagnostic evaluations for an average of one year before starting treatments” and seem to approve of this approach, even though MacKinnon’s previous research is on how assessments do not work.

According to The Atlantic,

Those of us who believe in LGBTQ-inclusive health care and bodily autonomy must recognize that some of our hard-earned wins may have introduced new uncertainties.

Here, the authors link the recent New York Times article on puberty blockers, an unscientific, ideologically posed dog whistle that has added fuel to debates around restricting gender-affirming care to minors across the U.S. Ky reports that members of her old detransitioner groups pushed back on the harmful myth that people who detransition were rushed into transition. Most were not rushed; their experiences with accessing transition-related care varied.

I imagine if you actually researched how detrans people came to transition, you’d find a diverse range of experiences, especially depending on when people transitioned.

Pitting Detransitioned People vs. Trans People

The authors state:

Unfortunately, some people who discuss their detransition on social media are met with suspicion, blame, mockery, harassment, or even threats from within the LGBTQ communities in which they previously found refuge.

First, trans people who are hostile to people who detransition are often also hostile to other trans people, including nonbinary and genderfluid people, who do not fit their narrow definition of what a “real” trans person is. Second, our experience with detransitioners is shaped mainly by their depiction in the media; those detransitioners who are regularly platformed are part of the anti-trans movement. Suspicion and blame within LGBTQ spaces after detransition does happen, but it’s often because of fear induced by the current political climate. While this isn’t fair to the detransitioner if they’re not anti-trans, it is an understandable response connected to ongoing trauma.

Ky explains:

In most other cases, trans people respond to harmful actions by detrans anti-trans activists and distinguish them from detrans people. Most of the time, when trans people were mad at me when I was a detrans woman, it was because I was a TERF and saying/doing things that hurt them. They were completely right to be upset with me and critical of my actions. And when I stopped being transphobic and started speaking out about my past actions, almost all trans people were very forgiving.

Trans-supportive people who have detransitioned are often supported by trans people, and trans people frequently voice their support of detrans people. The Atlantic ignores that mutual support between trans and detrans people and focuses on hostility, further skewing reality. Anti-trans people who have detransitioned are, naturally, going to encounter suspicion and anger from trans people. Ky’s experience follows that pattern:

My trans and queer friends completely supported me when I detransitioned, but I distanced myself from them when I got deeper into anti-trans feminism. I rejected the queer/trans community, not the other way around. This was pretty common among detrans TERFs I knew. Also, many detrans TERFs I knew were rejected by their former queer/trans communities after making blatantly anti-trans statements, like claiming that trans women are more likely to be rapists and abusers and calling that “male violence.” I also knew detrans TERFs who admitted that they were mean to trans people and got into fights with them because they were jealous of how those trans people were still transitioning. Some detrans TERFs still wanted to be on testosterone but had decided that doing so would be giving into internalized sexism, so they were taking out their frustration on trans men. Plenty of transphobic detrans people troll trans people all the time. It’s not hard to find examples of that. It’s just wild to me to frame this as trans people being mean to detrans people for no reason when you can easily find transphobic detrans people acting like assholes towards trans people completely unprovoked.

Lee points out that angry Twitter and TikTok responses from trans people are not representative of the general sentiment; one could argue that they are cultivated by algorithms feeding marginalized communities’ hate speech by design, something Tiktok is already known for doing. Instead of relying on social media anecdotes to fuel speculation about a manufactured rift, we should be doing academic research into trans people’s attitudes about detransition and detransitioners. Trans people are in no way being unreasonable when they recognize that detransitioned people who engage in anti-trans activism threaten them, and most trans people can distinguish between detransitioned people who are just living their lives versus those who engage in activism that attacks trans people, trans rights, and trans health care. Trans and detrans communities have the same or similar struggles, issues of regret, substandard care, and discrimination. There are many trans people interested in developing resources for detransitioners, while other groups claiming to support detransitioners are using them to support their anti-trans agenda.

The Atlantic discusses trans people attacking detransitioned people but not detransitioned people who attack trans people and medical transition. Ky says she instigated conflicts with trans people when she was a detransitioned radical feminist because it was an excellent way to spread her propaganda. Most of the time, when she got into conflicts with trans people, it was because of her transphobic beliefs and activism, not just because she was detransitioned. There was a massive difference in how trans people responded to her based on how deep she was in anti-trans ideology. When she started getting disillusioned with transphobic feminism and started becoming more accepting and respectful towards trans people, then trans people suddenly became a lot more open and interested in what she had to say.

A disproportionate number of detrans people featured in the media are anti-trans activists with an agenda to portray trans people and gender-affirming care negatively. They try to get into the media and do what they can to control public narratives about detransition. Journalists often fail to do background research to uncover this or omit to mention the person’s politics or their ties to anti-trans groups. It is also worth noting that mainstream media predominately portrays detransition negatively, including the people they interview, framing their narratives within the context of “regret” and “irreversible harm.” When detransitioned people speak up about experiences that do not match that general narrative, they are attacked, sometimes by their own covering journalists.

In The Atlantic, Valdes and MacKinnon claim, without citation:

Meanwhile, clinicians who receive threats of violence for assisting trans youth are vulnerable to developing myopic positions and overly optimistic clinical practices that ignore detransitioners’ accounts.

This is inaccurate. The immediate response has been fear and limiting or even shutting down much-needed health care services.

Detransitioners And the Ex-Gay Movement

The authors write, “Some trans-rights advocates have likened detransitioners to the ex-gay movement or described them as anti-trans grifters,” and link Ky’s Slate interview, in which she exposed her experiences with detrans communities. Ky likened her experience with a particular political subgroup of detransitioners to the ex-gay movement. We have previously compared the current platforming of anti-trans detransitioners to past ex-gay panics. The rhetoric around “detransitioners” is not dissimilar to that of the “ex-gay” movement, both insisting sexual or gender minorities are a “treatable disease.” Claiming that being trans can be caused by trauma is like the ex-gay movement claiming that being queer can be caused by trauma. These debates, naturally, often center on children. The Atlantic piece simply claiming that “trans-rights advocates” (itself a dog-whistle term) liken detransitioners to the ex-gay movement misrepresents the source it cites and fails to engage with the reality that there are ex-trans movements that parallel the ex-gay movement and even have direct overlap with it. This overlap-for example, Kathy-Grace Duncan, who is one of the amici on the joint anti-trans detrans amicus brief in Arizona and also connected to conversion therapy ministry Portland Fellowship, is becoming increasingly common as the prevalent narratives around detransition gain traction in both mainstream and religious media. Sure, individual detransitioners shouldn’t have malice assumed from their detransition—they’re not the reason why that association exists in the minds of trans people.

Ky coined the phrase “ideologically-motivated detransition” to distinguish between her experiences and other detransition experiences when she first started discussing her detransition as a conversion practice and tried from the start to make it clear that her experiences are not universal:

Framing me as if I was saying that all detransitioned people are like the ex-gay movement is frankly insulting. It also doesn’t consider that publicly naming detransition as a conversion practice for a survivor can be terrifying, and you can face retaliation from your old community. Doing that interview with Slate wasn’t easy; I knew people from my old group would be pissed at me, and some did lash out. There are hardly any resources for trans survivors of conversion practices or information about it. There’s not much visibility. It’s like MacKinnon never considered how that statement could negatively impact survivors of detransition as a conversion practice. Two study participants in MacKinnon’s research also talk about detrans groups that were toxic and transphobic. It’s bizarre and frustrating to read what his research participants say about detrans groups like my old one, feel relief and like I’m less alone, and then read MacKinnon dismissing experiences like mine. What I say and what some of his research subjects say corroborate each other; they don’t conflict.

What About the Children?

It is no accident that trans youth are at the epicenter of our “trans debates”; children are the sentimental stand-in for the nation. Invoking hypothetical protections for children draws attention from real political concerns and demands. There are quite a few articles fear-mongering about children and detransition while solely featuring detrans adults. Trans historian Prof. Jules Gill-Peterson explains this further:

The politics of “protecting” the innocent white child have rationalized the disposability of entire populations, like immigrants, the descendants of enslaved people, criminals, people with disabilities, and so-called deviants. Today we are witnessing trans children’s addition to this list. The resulting eugenic arithmetic is far from hidden: Trans children, according to this ideology, are not innocent due to their supposed corruption by “gender ideology” and medicalization, which are in reality indictments of their self-knowledge and active trans desire; they therefore must be ejected from the boundaries of the nation in order that “women and girls” be protected from them, or protected from transness. This is how a bill that claims to promote safety or ensure fairness can save itself from the obvious objection that in fact it does the very opposite.

Groups like the ADF need to characterize trans kids as “new” and their care as experimental and dangerous (they’re not, and it’s not); turning our lives into a debate and reframing our right to exist as an ideology is entirely the point.

Desistance as a Disease Model

Detransition, when defined as stopping social, medical, surgical, and/or legal changes a person makes to affirm a gender different from the one they were assigned at birth, can apply to all age groups. However, another term is used to describe the phenomenon of detransitioning before puberty (i.e., before any medical or surgical gender affirmation steps can be taken): desistance. We have previously discussed the pervasive and debunked desistance myth; it is now essential to discuss the etiology of the term. In 2003, Kenneth Zucker started applying the term to trans youth after reading a paper on the persistence and desistance of ODD (oppositional defiant disorder) in children. Zucker claims, “at the time, the terms sounded pretty cool to me.” He neglects to mention that “desistance” comes from criminology; desistance studies are about crime prevention. Scientists study the efforts that will make people desist from committing crimes.

A 2022 systematic review examined the database of studies on desistance in trans youth. 30 studies explicitly used the word ‘desistance’ though only 13 defined it. Most studies were ranked to have a significant risk of bias and were not driven by an original hypothesis. Those who defined “desistance” agreed that trans children who desist are those who identify as cisgender after puberty, with the assumption that they will continue to identify as cisgender into adulthood, or those whose gender dysphoria resolved before puberty, even though the absence of gender dysphoria does not indicate a cisgender identity. None of the definitions allowed for nonbinary or genderfluid identities. These concepts were derived from biased research from the 1960s to the 80s and poor-quality research in the 2000s. Most studies examined socially and economically privileged white trans youth. Desistance research is clinically irrelevant, steeped in bias, and aimed at predicting future gender identities. Health professionals are best served to support trans youth now and respect their asserted gender identities.

Who is Speaking for Whom

Ky implores:

There’s something really sketchy about claiming to speak on behalf of other people who didn’t appoint you as any kind of spokesperson or representative. Why should MacKinnon and Valdes be the ones to advocate for people who’ve detransitioned? What have they done to earn that position, and why should they be trusted to represent detransitioned people? The cynical side of me wonders if they’re trying to cash in on the “moral panic” surrounding detransition. They didn’t even bother to contact Chris Beck, who they claim to speak on behalf of.

As someone who detransitioned and who still considers that period a significant time in my life, I don’t like how detransition is represented in this article at all, and not just because they deny some of my experience while citing the Slate article. I never saw detransition as a bad outcome, and I fought against that view. I saw how I was treated “less than” as a detrans person by people who viewed detransition that way. I associate that view with being seen as less than others and people trying to use me. It’s very objectifying and oversimplifies a lot. The people who caused me the most problems and stress weren’t trans people but cis people. Transphobic cis people treated me much, much worse than trans people ever did. This article wouldn’t have created any positive change for me as a detrans woman and wouldn’t help people understand what detransition was like for me. If anything, it just strengthens misconceptions about what detransition is like for many people.

Studies on Detransition

The other studies linked in The Atlantic article are Guerra et al. 2020, who studied a cohort of 796 patients in Spain between 2008 and 2018. There was a total of 8 documented detransition cases, or 0.1%. Ascha et al. 2022 was a study on top surgery and chest dysphoria that does not measure regret or detransition. Hall et al. 2021 noted a regret rate of 1.14% (2 out of 175 cases at a UK national adult gender identity clinic). They mention that 12 out of 175 cases “fit criteria for detransitioning”; however, only 9/12 had evidence of discontinuing hormones, two had no documented information about hormones, and one continued with hormones. Boyd et al. 2022 note a 9.8% rate of detransition, characterized like this: “Four transmen had comments in the records that related to a change in gender identity or detransitioning (4/41, 9.8%): “Would like to gradually detransition”; “No longer wish to live your life as a male”; “Has decided to detransition…Feels comfortable having decided to dress and appear more feminine;” “Feels it was a mistake, identifying as non-binary now.” Of note, these are clinician comments, not patient remarks, and identifying as nonbinary does not equal detransition.

More studies on detransition are worth mentioning as they add to the research database. The Royal Children’s Hospital Gender Service in Victoria began treating transgender youth in 2003 and has taken in 701 patients for assessment. The court found that 96% of all youth diagnosed with Gender Dysphoria from 2003 to 2017 continued to identify as transgender or gender diverse into late adolescence. No patient who had commenced gender-affirming hormones had sought to transition back to their birth-assigned sex. Similarly, de Vries’ long-term study of trans youth found no pattern of detransition or regret. Nor did a study of 75 German trans youth have any who expressed regret. A 2020 study of 143 Dutch transgender youth who started blockers found that only 5 (3.5%) discontinued gender-affirming treatment. A 2022 retrospective review of Spanish trans minors found that out of a sample of 124 diagnosed with gender dysphoria, 97.6% persisted over 2.6 years (on average). A long-term (5-year) study of 317 trans youth (average 8.1 years) who socially transitioned found that most youth identified as binary transgender youth (94%), including 1.3% who retransitioned to another identity before returning to their binary transgender identity. 3.5% identified as nonbinary, and only 2.5% identified as cisgender. UK GIC clinicians conducted a records review of 3,398 transgender patients at the Charing Cross, Tavistock, and Portman clinics. They found only two (.06%) who had detransitioned due to regret or deciding that they were not transgender.

Similarly, a Dutch study of 6,793 patients who medically transitioned found that only 7 (.1%) regretted transition because they decided they were not transgender. A 2021 study of youth who ceased puberty suppression found that many were glad to have had it available because it safely offered them time and space to explore their gender identity. Regret among those trans teens undergoing chest reconstruction is also rare. The most recent study found that less than 1% of trans men who had chest reconstruction before 18 had regrets. Conversely, approximately 5% of cisgender women who undergo breast reduction experience regret, and this is considered by plastic surgeons to be extremely low.

The Answer Is…Gender-Affirming Care

Valdes and MacKinnon state,

Upholding the dignity and diversity of trans, nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming populations should not be at odds with a data-informed medical approach that seeks to maximize positive outcomes for all.

Agreed. Gender-affirming care is a data-informed medical approach; it may be worth stopping pretending it doesn’t exist. In this approach, there is no expected outcome; no one is directed in one way or another. Instead, patients are affirmed in their current gender.

Ky asks:

What if we just accepted that some people detransition, stopped scaremongering about it because that isn’t helpful to detrans people, and provided resources for people who detransition so they could get on with their lives? These would include better medical treatment, providing help with changing legal documents, showing positive portrayals of detransitioned people just living their lives that are completely detached from anti-trans rhetoric support groups that aren’t run by TERFs or right-wing Christians, etc. MacKinnon says he wants to use the ‘support detrans’ framework while doing his research; it would be good to see him take the same approach while engaging with the media.

The Atlantic asserts:

For patients to give informed consent to medical treatment, they need to know about the range of possible outcomes.

Well, yes: that defines the process of informed consent. In an informed consent setting, patients will be told that most people who detransition do not regret transitioning…right?

Valdes and MacKinnon claim that trans health experts urge deceleration for kids, linking to an article featuring Laura Edwards-Leeper and Erica Anderson, health professionals who oppose gender-affirming care. Edwards-Leeper has been endorsing books such as Mark Yarhouse and Julia Sadusky’s Gender Identity and Faith. This book includes a scale of interventions for treating gender dysphoria, from “least invasive”—prayer and other spiritual practices—to “most invasive”—social and medical transition, which is not to be approached unless nothing else works. Erica Anderson, meanwhile, is explicitly on the payroll as an expert witness for groups aiming to criminalize gender-affirming care. She has spoken in defense of and will serve as a witness for Jamie Reed, despite Reed potentially violating HIPAA and causing undue distress to trans youth and their families, and despite Reed’s lawyer, Vernadette Broyles, being a member of the Alliance Defending Freedom, a recognized hate group. She is neither a neutral actor nor necessarily a reliable perspective in this space. These developments were not known at the time Valdes and MacKinnon cited Anderson—but the fact that she was their example of a critical professional tells of how generalizable their claims are.

The authors conclude The Atlantic article with the following:

Gender-affirming care must be available to those who need it. But our community must also advocate for the research to help transitioning patients thrive in the long run—regardless of their individual outcome.

We agree. This is what those of us involved in trans health care research already do. This article—whatever this is—does not add anything constructive to the current conversation. Bioethicist Florence Ashley argues that the goal of preventing regret through the gatekeeping of hormones is not only dehumanizing but also only makes sense “within a framework that sees trans people as mentally ill.”

How Does One Take Detransitioners Seriously?

As Lee notes:

The fact of the matter is that those of us who do not align with GC rhetoric surrounding detransition, even if we have experience with the subject, get no voice at the table. Not in the press, not in legislation, and not in this article. Do you want to take detransitioners seriously? Listen to people who aren’t calling for care to be removed. Listen to people who have no choice in detransitioning or who undergo conversion practices. Listen to people who are forced to detransition because of these policies being proposed. And for the love of God, listen to those of us who got out of anti-trans circles because we’ve been trying to warn you about this nonsense for years.

Decisions about how to represent detransition in the media, including detransition-related research, influence how detransition is written about and conceptualized elsewhere. Media portrayals impact legislation more than studies, and the GOP uses media coverage to fill out cherry-picked research on Letters to the Editor in court justifications, giving the impression that attacks on trans health care are justified by both science and public opinion.

Detransition research plays a key role in anti-trans activism; some of it is even performed by transphobic people. We need to ask the question: how can we create scientifically valid and useful research? We can’t just accept research from Littman and Vandenbussche at face value and expect to be able to help detransitioned people. To help detransitioners, we must dissect that research and point out its many harms and flaws. That research could be used to understand how the anti-trans movement creates disinformation. Additionally, scientific research on regret rates does not support the idea that more people are detransitioning and can’t talk about it for fear of retaliation.

This article misrepresents the research on detransition to make it seem more common than the research suggests. Detransition regret is not nearly as common as regret for other medical procedures, so why is it more important?

There is a possibility that research into detransition could dispel fears about it or prove that concerns about preventing regret are overblown, especially given that MacKinnon’s study found that most of his subjects did not regret transitioning. It should be suspicious when research conforms so closely to anti-trans media narratives about detransition; even MacKinnon’s own research does not conform to those narratives. The Atlantic article, and others in which MacKinnon is quoted, take a stance toward preventing detransition; however, MacKinnon’s research rejects this approach, arguing against research that seeks to prevent detransition and for research to help develop more support and resources for people who detransition. Research into supporting detransitioners is much needed and could help improve the quality of life for people who detransition. We need more scientifically sound research into detransitioning and retransitioning, including research about detransitioned people/groups that are part of the anti-trans movement and promote conversion practices and research that truly reflects the group’s needs (s) being surveyed. We need less stigma against detransition in the trans community, but we also need to help people fight against transphobic detrans activists. We need people to be aware that there are anti-trans groups seeking to promote detransition as a form of conversion therapy, that some detrans groups work to recruit trans people and indoctrinate them into anti-trans ideologies, and that this can cause severe and lasting harm. We want there to be more resources for people who’ve been harmed by detransition as a conversion practice. We want ideological detrans groups and their political activism to be factored into public discussions about detransition. Those groups are trying to shape public discourse and media representation of detransition, and they deserve critical scrutiny.

In a recent video, right-wing pundit Michael Knowles stated that transgender people are “not a legitimate category of being and therefore cannot be the target of genocide.” He has since called for the eradication of “transgenderism.” Over 220 bills targeting trans people have been introduced in state legislatures in 2023. Arkansas Senate Bill 270 bans trans adults from using the bathroom that aligns with their gender and further bans trans adults from being in the bathroom at the same time as a child under 18. Similar bills just passed in Florida and North Dakota. Kansas’ bathroom bill broadly applies to any separate spaces for men and women, attempting to erase trans people and refusing to acknowledge the existence of genderfluid, gender nonconforming, and nonbinary people. Tennessee officially passed the first drag ban; at least 14 other states have filed anti-drag bills this year. We live in a time of escalating onslaught against trans people, with bad-faith actors creating a moral panic that has been telegraphed and explicitly detailed over the last several years. To stop this, we need to take trans people seriously. Depathologize trans identities. Stop dehumanizing trans people and criminalizing their bodies. LGBTQ rights are human rights.

All of these are necessary preconditions to take detransitioners seriously, as well. Currently, the news media does not, and sadly, this article from The Atlantic does nothing to solve that problem. The news media only features detransitioners as a rhetorical foil to happily transitioned trans people. It platforms the most reactionary, right-wing, and transphobic detransitioners who oppose youth care on principle and assume that because it wasn’t right for them, it’s wrong for anyone. And it does so without regard to how right-wing groups, currently attempting to criminalize that care, will use it to advance their agendas at the expense of both happily transitioned trans people and detransitioners—however they may be defined. Valdes and MacKinnon’s work is not meritless: detransitioners do matter, transgender people shouldn’t disparage them for existing, and their needs need to be taken into account by practitioners. However, by failing to properly contextualize the landscape detransitioners face, by taking questionable sources at their word, and by failing to account for who exactly poisoned the discourse around transition, detransition, and retransition, this article fails to follow its prescription.

Addendum 5/20/2023: honoring the request of The Atlantic article author Kinnon MacKinnon, we have made the following corrections: changed authorship order from MacKinnon and Valdes to Valdes and MacKinnon, per MacKinnon’s concern about first and second author roles, throughout the post; corrected four unfortunate instances of misspelling Valdes.

Separately, upon noting a name change on her article and Rutgers University profile, we have updated Valdes’ first name to the correct one.

Authors

Ky Schevers

Ky (she/her) is one of the duo behind Health Liberation Now!, who advocate for equitable access to health care and expose the weaponization of detransition narratives. Under the name CrashChaosCats, Ky engaged in anti-trans activism as a detransitioned radical feminist from 2013 to late 2019. Ky used to work hard to get into the media to shift the public conversation about transition and detransition. As someone who was harmed by such groups and caused harm while she was part of them, Ky knows the damage detrans groups and activism cause. She deeply regrets how she manipulated the media to spread anti-trans propaganda and promote conversion practices. She agrees with trans people who criticized the articles she appeared in, particularly Katie Herzog’s infamous 2017 article, The Detransitioners, which is still cited widely by anti-trans activists and used as propaganda.

Lee Leveille

Lee (she/her and he/him) is the other half of Health Liberation Now! and was the founding Vice President of the Gender Care Consumer Advocacy Network (GCCAN), a self-proclaimed “non-partisan, non-ideological collaboration between trans and detransitioned people to advocate for better health care.” However, he resigned in protest after seeing the impact his and similar groups have on trans health narratives.